In this interview, Alain Badiou focuses on the concept of the migrant, or the sans-papiers. Badiou discusses the importance of this concept in his previous work and for contemporary politics.

Dissent – Art

In this interview, Alain Badiou focuses on the concept of the migrant, or the sans-papiers. Badiou discusses the importance of this concept in his previous work and for contemporary politics.

The art of thinking

Today the most civilized countries of the world spend a maximum of their income on war and a minimum on education. The twenty-first century will reverse this order. It will be more glorious to fight against ignorance than to die on the field of battle. The discovery of a new scientific truth will be more important than the squabbles of diplomats. Even the newspapers of our own day are beginning to treat scientific discoveries and the creation of fresh philosophical concepts as news. The newspapers of the twenty-first century will give a mere “stick” in the back pages to accounts of crime or political controversies, but will headline on the front pages the proclamation of a new scientific hypothesis.

Progress along such lines will be impossible while nations persist in the savage practice of killing each other off. I inherited from my father, an erudite man who labored hard for peace, an ineradicable hatred of war. Like other inventors, I believed at one time that war could he stopped by making it more destructive. But I found that I was mistaken. I underestimated man’s combative instinct, which it will take more than a century to breed out. We cannot abolish war by outlawing it. We cannot end it by disarming the strong. War can be stopped, not by making the strong weak but by making every nation, weak or strong, able to defend itself.

Hitherto all devices that could be used for defense could also be utilized to serve for aggression. This nullified the value of the improvement for purposes of peace. But I was fortunate enough to evolve a new idea and to perfect means which can be used chiefly for defense. If it is adopted, it will revolutionize the relations between nations. It will make any country, large or small, impregnable against armies, airplanes, and other means for attack. My invention requires a large plant, but once it is established it will he possible to destroy anything, men or machines, approaching within a radius of 200 miles. It will, so to speak, provide a wall of power offering an insuperable obstacle against any effective aggression.

If no country can be attacked successfully, there can be no purpose in war. My discovery ends the menace of airplanes or submarines, but it insures the supremacy of the battleship, because battleships may be provided with some of the required equipment. There might still be war at sea, but no warship could successfully attack the shore line, as the coast equipment will be superior to the armament of any battleship.

I want to state explicitly that this invention of mine does not contemplate the use of any so-called “death rays.” Rays are not applicable because they cannot be produced in requisite quantities and diminish rapidly in intensity with distance. All the energy of New York City (approximately two million horsepower) transformed into rays and projected twenty miles, could not kill a human being, because, according to a well known law of physics, it would disperse to such an extent as to be ineffectual.

My apparatus projects particles which may be relatively large or of microscopic dimensions, enabling us to convey to a small area at a great distance trillions of times more energy than is possible with rays of any kind. Many thousands of horsepower can thus be transmitted by a stream thinner than a hair, so that nothing can resist. This wonderful feature will make it possible, among other things, to achieve undreamed-of results in television, for there will be almost no limit to the intensity of illumination, the size of the picture, or distance of projection.

I do not say that there may not be several destructive wars before the world accepts my gift. I may not live to see its acceptance. But I am convinced that a century from now every nation will render itself immune from attack by my device or by a device based upon a similar principle.

At present we suffer from the derangement of our civilization because we have not yet completely adjusted ourselves to the machine age. The solution of our problems does not lie in destroying but in mastering the machine.

Innumerable activities still performed by human hands today will be performed by automatons. At this very moment scientists working in the laboratories of American universities are attempting to create what has been described as a “thinking machine.” I anticipated this development.

And unless mankind’s attention is too violently diverted by external wars and internal revolutions, there is no reason why the electric millennium should not begin in a few decades.

Excerpted from Liberty, February 1937

“I try to let the film think.”

Harun Farocki (9 January 1944 – 30 July 2014) was a filmmaker, author, and film theorist. He was deeply influenced by Bertolt Brecht and Jean-Luc Godard. Farocki’s films investigate the processes through which images and the messages they carry are constructed, transmitted, and perceived; as well as the ability of recorded images to convey the realities of war.

The Anti-fascist school booklet was devised as a learning notebook for reading, writing and calculation, but also as an artistic publication by the Popular Front Government at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. The Cervantes Institute (Instituto Cervantes) organised an exhibition on this historical document, which also served as a tribute to its creators: the Polish-born graphic designer Mauricio Amster and the Berlin photographer Walter Reuter.

Psychoanalysis and the New Rhetoric is a collaborative work emerging from several years of conversations between Adleman – a rhetorician – and Vanderwees – a psychoanalyst. Their dialogue represents a thoughtful fusion of psychoanalytic practice and theory with new rhetoric, rather effectively combining the work of Freud, Burke, and Lacan as main theoreticians, with many others also included. Rhetoric and psychoanalysis are disciplines that have been, or still are, on the margins of established scientific and institutional domains.

Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, the title of the 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, is drawn from a series of works started in 2004 by the Paris-born and Palermo-based collective Claire Fontaine.

Foreigners Everywhere was a series of neon signs in several different languages. Named for Stranieri Ovunque, an anarchist collective from Turin, the work embodies and projects the ambivalence of their name into various sites and contexts. Lacking context, the neon suggests a factual statement, xenophobic threat, and evokes the estrangement of feeling foreign in a global society, a circumstance legible by the targeted populations.

https://www.labiennale.org/en/news/biennale-arte-2024-stranieri-ovunque-foreignerseverywhere

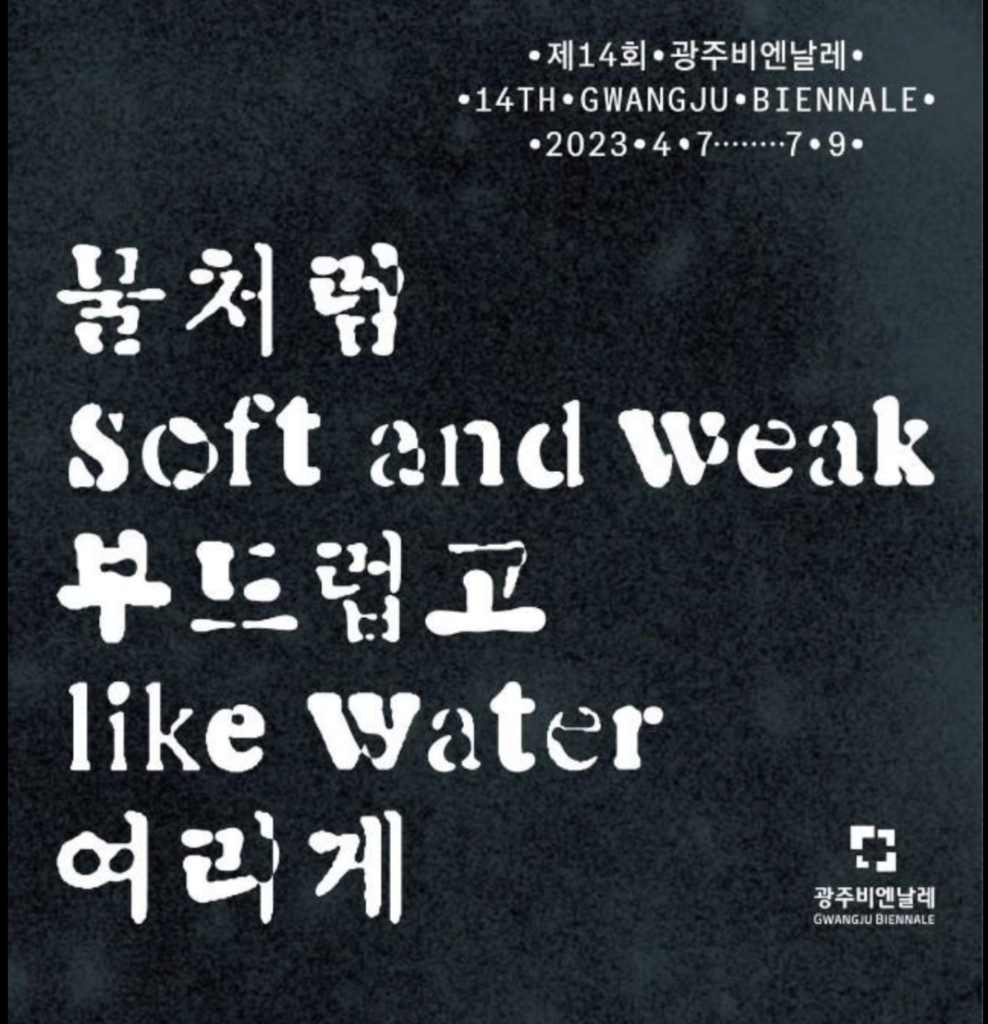

7 April – 9 July 2023

The 14th Gwangju Biennale proposes to imagine our shared planet as a site of resistance, coexistence, solidarity and care by thinking through the transformative and restorative potential of water as a metaphor, a force, and a method. Soft and weak like water celebrates an aqueous model of power that brings forth change, not with an immediate effect but with endurance and pervasive gentleness, flowing across structural divisions and differences. Embracing contradictions and paradoxes – as “there is nothing softer and weaker than water, and yet there is nothing better for attacking hard and strong things” (Dao De Jing, chap.78) – the Biennale’s theme highlights the capacity of art to permeate deep into the individual and the collective, which enables us to navigate through the complexities of the world with a sense of awareness and direction.

Planetary Times

Considering the shared future of human civilisation requires a broad perspective that encompasses different or even conflicting views across borders. By exploring artistic practices that respond to the ongoing crises of humanity through the lens of relational cosmology that emphasises change, fluidity, and indeterminacy, Planetary Times imagines the Earth as a site of shared connections and removed boundaries that is entangled with the era of the Anthropocene. Such imaginary crossroads reveal a connected planetary viewpoint, beyond the perspectives that centers the human. The crisis of civilization brought forth by climate emergency, manifest in unprecedented droughts, forest fires, and floods around the world, prompts a fundamental reconsideration of unequal models of production and consumption, multinational corporations and late capitalist economic infrastructures and emphasises the significance of solidarity across borders. By presenting works that propose diverse and multifaceted responses to the crises that affect the entire world, this node sheds light on a ‘planetary’ perspective that moves beyond the ‘global’. In so doing, it seeks to move away from homogenous perspectives to value the lived, everyday experiences of artists and their activist possibilities.

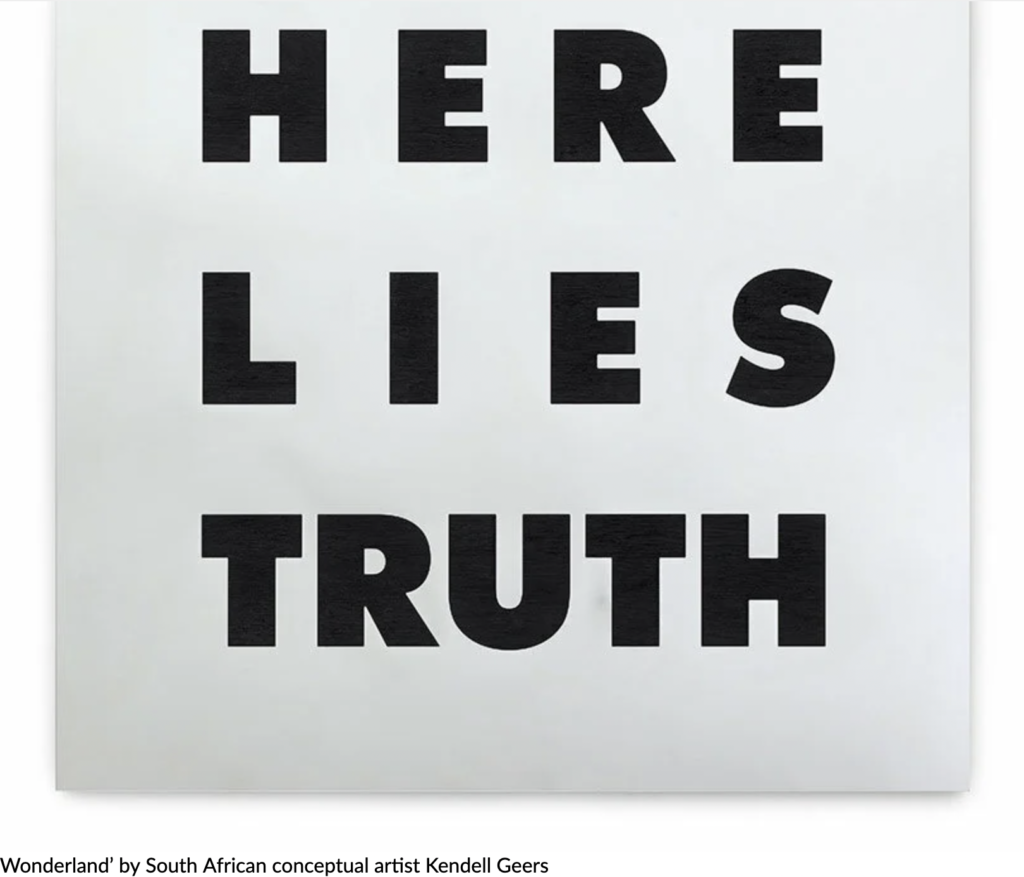

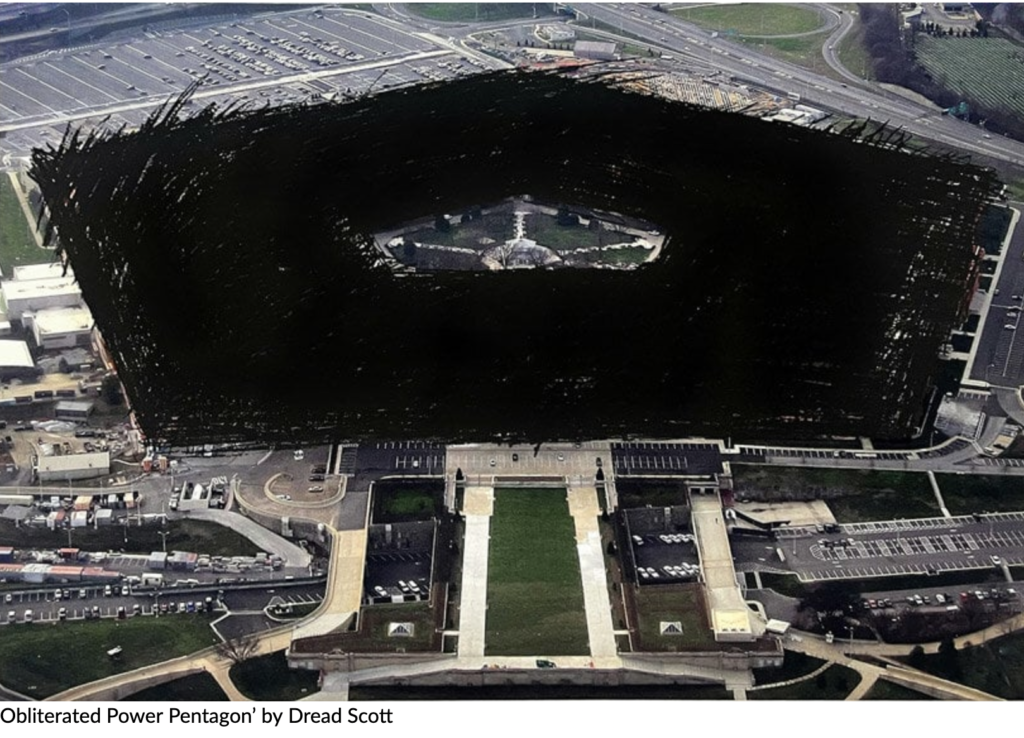

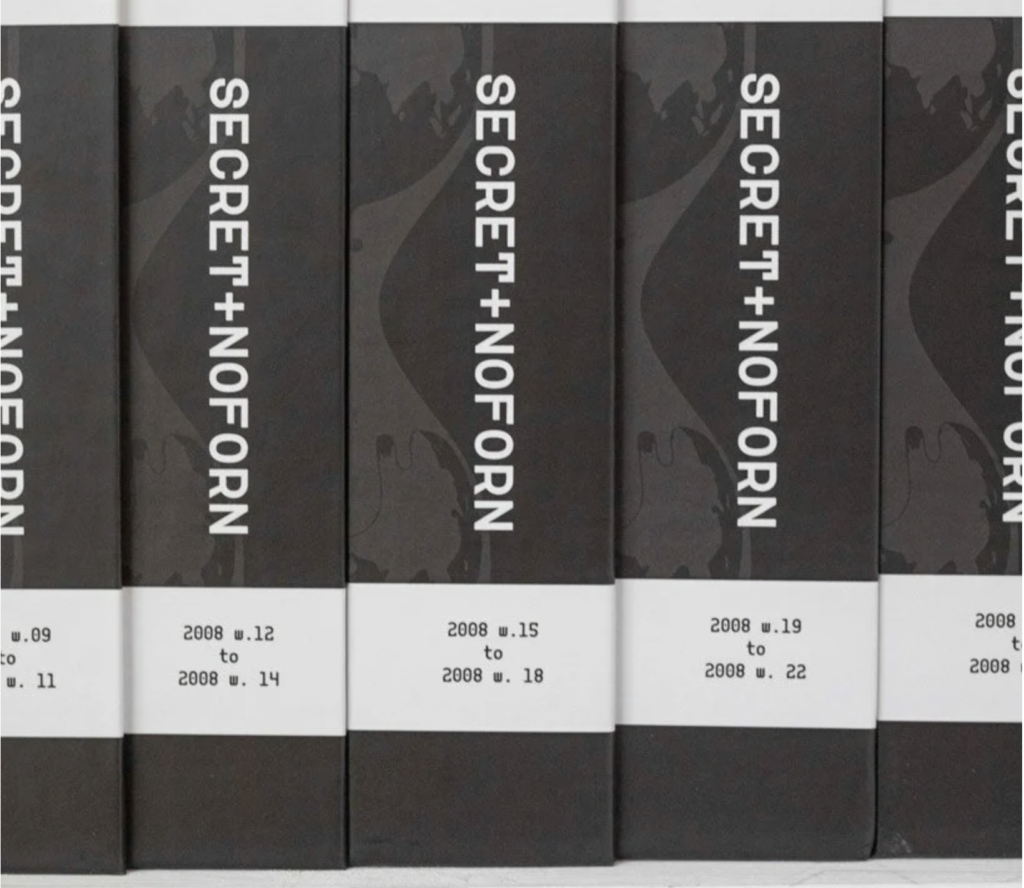

The exhibition ‘States of Violence’ exposes top government cables leaked by Julian Assange and brings together the work of leading artists and agitators, unveiling forms of government oppression. The rebellious show is presented by the non-profit London-based arts organization a/political, marking an outstanding collaboration with WikiLeaks — the well-known NGO that operates a whistleblowing news site.

‘States of Violence’ battles for our freedom of speech in the modern era we are going through, exposing top-secret government cables and classified media, never before available in hardcopy in the UK. The works created by iconic names such as Ai Weiwei, Dread Scott, and The Vivienne Foundation, among others, put the spotlight on global power structures, releasing material for the darkest truths of our modern reality. The display also includes hard copies of documents leaked in 2010 by Wikileaks whistleblower and activist Julian Assange, also fighting for his freedom, as he has been detained at London’s high-security Belmarsh Prison since 2019.

A new dawn for politics is a collection of Alain Badiou’s writings from 2016 and 2020 which comprise essays and lectures on the ideological and political situation worldwide and in France.

https://www.tankebanen.no/inscriptions/index.php/inscriptions/issue/view/10