Monday 26 April 1937

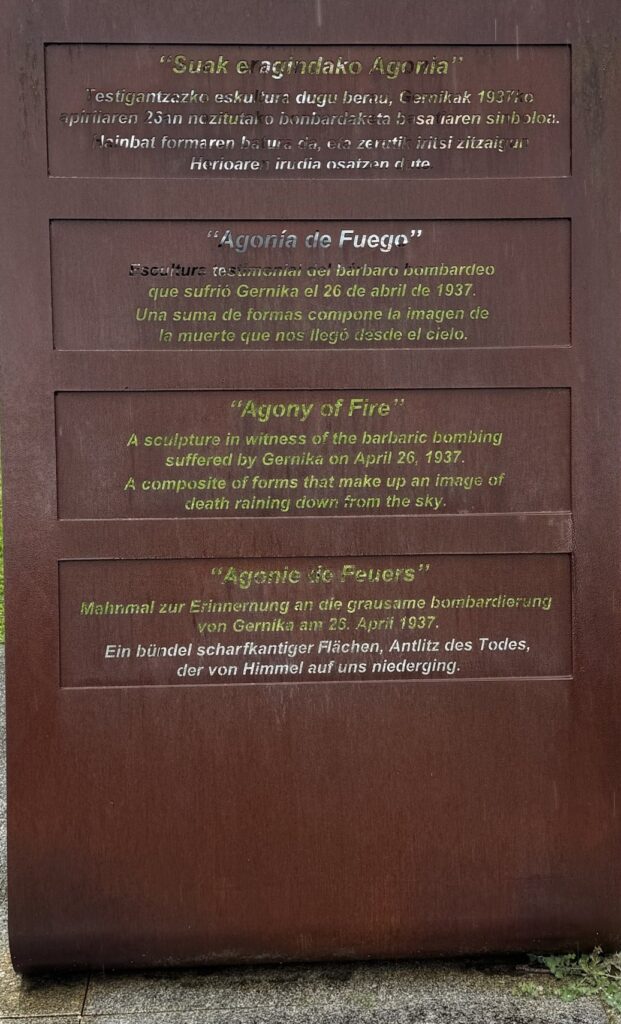

From 4.40 to 7.45 in the late afternoon of Monday 26 April 1937, the small Basque town of Guernica was destroyed by sustained bombing attacks by Hitler’s Condor Legion and Mussolini’s Aviazzione Legionaria. It was carried out at the behest of Francisco Franco’s rebel Nationalist faction under the code name Operation Rügen. The operation was supervised by Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, the Condor Legion’s chief of staff, a brilliant and ruthless Prussian aristocrat with a doctorate in aeronautical engineering. A cousin of the First World War fighter ace ‘the Red Baron’ Manfred von Richthofen, Wolfram had planned the entire operation as an experiment in terror – as he would later mastermind the Blitzkrieg in Poland and France. His choice of projectiles aimed to cause the greatest possible number of civilian victims. A combination of explosive bombs and incendiaries rained on the residential sector of the town, which was largely made of wood. And to prevent the fires being put out, the municipal water tanks and the fire-station were the first targets. Terrified civilians fleeing to the surrounding fields were herded back into Guernica by the machine-gun strafing of Heinkel He 51 fighters that circled the town in what Richthofen called “the ring of fire”. Monday was market day in Guernica. Between the townspeople, refugees, peasants bringing goods to the market, and train loads of people from Bilbao coming to buy food, there were at least 10,000 people crammed into the town that day. They were attacked by 28 German and three Italian bombers together with 10 Heinkel He 51 and 12 Fiat CR32 biplane fighters and possibly six of the first ever Messerschmitt Bf109s. It was an operation on a scale that could hardly have been organised by the Germans behind the backs of the Spanish staff, with whom there was, in any case, constant liaison. The town had no anti-aircraft defences.

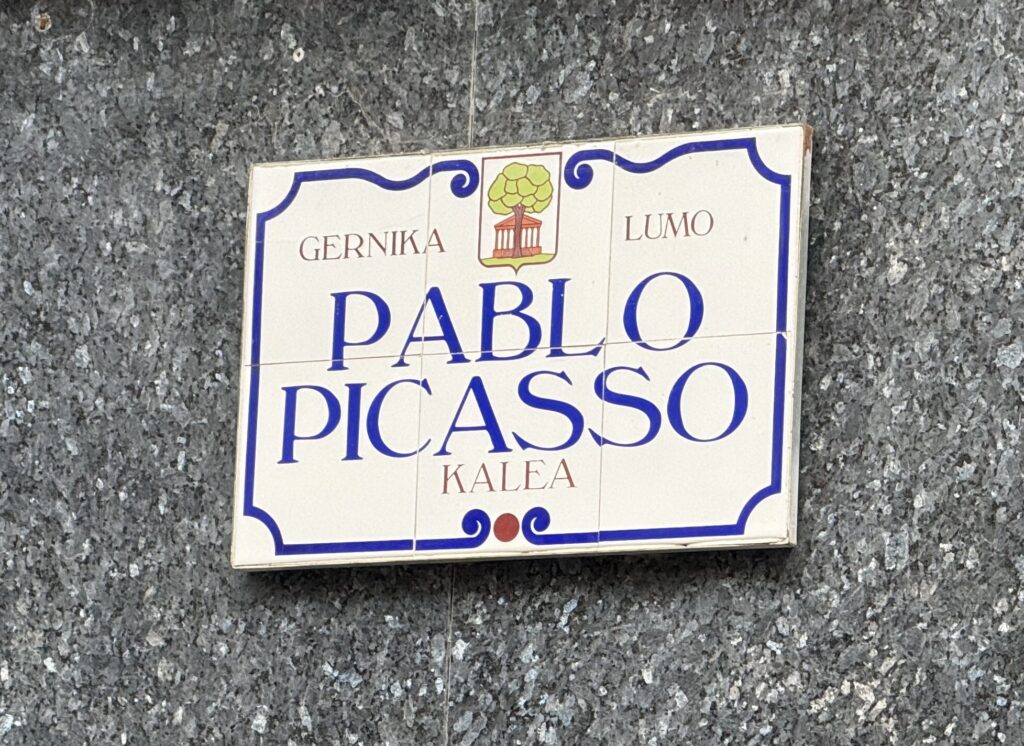

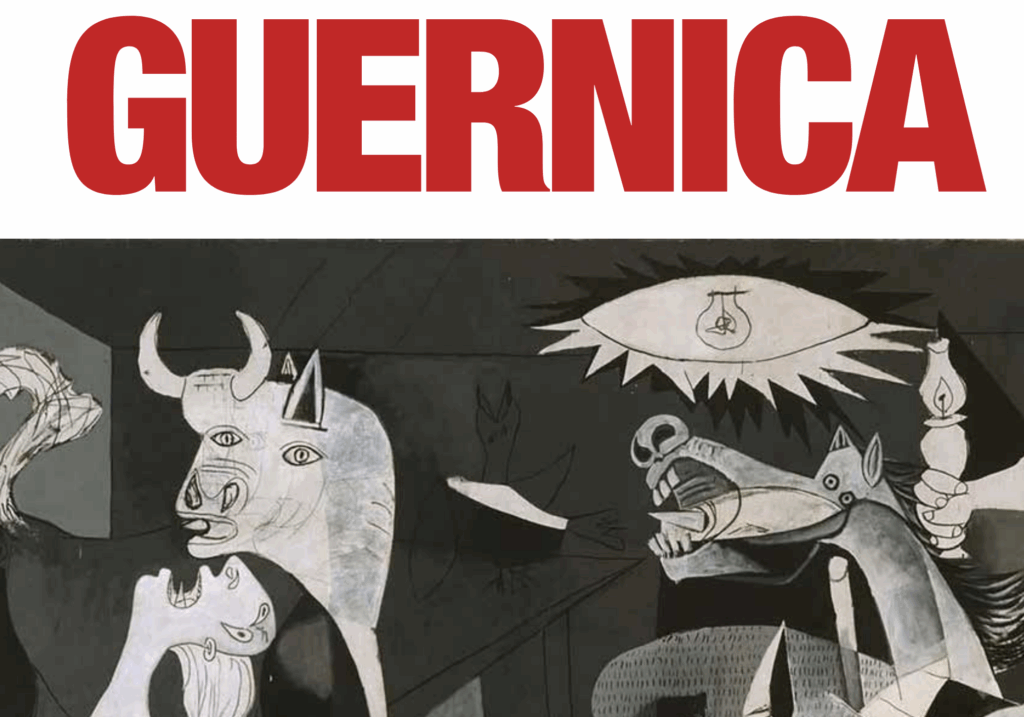

Largely thanks to Pablo Picasso’s searing painting, Guernica is now remembered as the place where a new and horrific modern warfare came of age. Picasso had previously avoided creating explicitly political art but the Spanish Republic was keen to get the world’s most famous artist to identify himself with its cause. In January 1937, he responded positively to an invitation to contribute to the Spanish pavilion at the World Fair in Paris scheduled for later in the year. That contribution would be Guernica. In fact the painting, begun on 1 May, four days after the bombing, is not just about what happened in the Basque town. There were three prior influences: the savage bombing of Madrid in October and November 1936 and again throughout April 1937; the suffering of refugees who were bombed and strafed as they fled in February 1937 from Picasso’s native Málaga to Almería; and the bombing of Durango on 31 March.